The combine harvester revolutionises the grain harvesting sector

Encouraged by the success of the knotter, August Claas and his brothers turned their attention to further development projects. They were particularly fascinated by the combine harvesters used on farms in America. The Claas brothers were firmly convinced that this technology would also become established in Europe. In 1936, they brought the first combine harvester specifically designed for European conditions onto the market. The combine harvester was to change the face of crop farming forever, as no other machine had done since the tractor, and it also marked a turning point in the story of CLAAS.

“Whereas the last century was defined by power engineering innovations, with coal, oil and electricity, in the coming century it will be agriculture, and particularly the combine harvester, that defines the world view of our species. The enormous changes that are imminent, and in some cases already happening, will impact not only on farmers, but also on industry, business and the political sphere”

- Prof. Dr. Karl Vormfelde, 1930

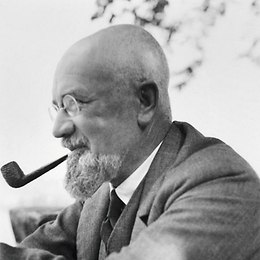

Professor Karl Vormfelde played a pioneering role in the development of the combine harvester for European conditions. In the 1930s, he headed the Institute for Agricultural Technology at the University of Bonn-Poppelsdorf. He had observed the major cost savings the use of combine harvesters was bringing for farmers, particularly in the USA, Canada, Argentina and Australia. Those countries’ agricultural sectors had become much more highly developed as a result. In the years from 1913 to 1927 alone, they almost doubled their grain exports, with far-reaching consequences for world grain prices and the farming sector in other countries.

“We are seeing huge and far-reaching changes in the structure of the agricultural sector across much of the world in the post-war period. It is only in the last five years that these regions have really started to develop, and the extent of their further advances and the implications for farming here in Germany can only be guessed at at this stage”, Vormfelde wrote in an essay published in 1931. There was only one conclusion to be drawn from his critical analysis of agricultural trends in Germany and abroad: “So we need to be harvesting with combine harvesters and tractors in Germany as well.”

Prejudices and problems regarding the new technology

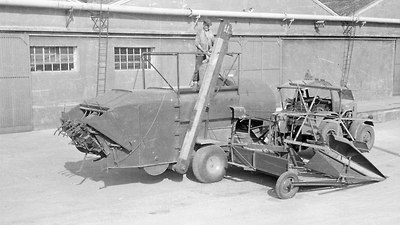

A forward-thinking but extremely daring design. Initial tests on the “Brenner” CLAAS PTO combine harvester were something of a disappointment.

This visionary idea that started to germinate in the minds of a select few already in the late 1920s was actually not all that new. Large numbers of combine harvesters had been working the fields in North America for a considerable time already. The German imperial Agricultural Equipment Committee (Reichskuratorium für Technik in der Landwirtschaft) had also recognised this need, and had carried out some experiments with the machines of American firms in Germany – but without success. The grain in Europe had much longer stalks, in many cases had much higher moisture levels than in the USA, and because of unfavourable weather conditions was often lying flat on the field surface. The American combine harvesters proved unable to cope with these harvesting conditions. The stalks wrapped around the machine drums, resulting in constant breakdowns.

So Vormfelde’s calls for increasing mechanisation in agriculture initially went virtually unheard, in the face of the reservations and doubts in the minds of German researchers and farmers regarding the combined reaping and threshing process. The established agricultural machine industry was also understandably reluctant to see any major changes in the situation. They were still earning a good return on their stationary threshing machines, and felt no desire to engage in risky experimentation with the new “direct harvesting process”. Another obstacle was public acceptance of the new machine in a country that was still in recession after the Great Depression, and had six million unemployed to cater for. Was this really the time for a machine designed to replace human labour?

Accordingly, Vormfelde found that the task of convincing public opinion in general, and particularly the leading producers of reaping and threshing machines, was simply impossible. Yet he still felt he was on the right track with his idea. Finally, one day he said to his research assistant, Dr. Walter Brenner: “Instead of knocking on the door of the big firms who have already turned us down, let’s go to the small operators – the Claas brothers, for example. I know the oldest brother, Bernhard Claas, personally. And August Claas, his younger brother, is an optimist and a really capable operator who isn't afraid to take risks.”

The task: to build a functioning machine for European conditions

In 1930, the 31-year old Walter Brenner, as suggested by his supervisor, went to pay a visit to the Claas brothers in Harsewinkel. CLAAS and Bonn University lost no time in finalising the deal, and, soon afterwards, Brenner came to work for CLAAS. His task was to develop a combine harvester that was fit for European conditions.

In his remarks recorded at the 75th birthday of August Claas, Brenner recalled the difficult beginnings of the combine harvester development project at that time:

“Like every big achievement, our work on the construction and development of the combine harvester started on a very small scale, with many hesitations along the way. In the initial years (1932–34), we managed to manufacture only one or two experimental machines a year, which were less than completely successful, but taught us many valuable lessons. The initial phase was devoted solely to experimenting with threshing drums, which were a new concept at this stage, because we fitted the drums with a long 25-metre belt, which gave us precise figures for their performance in the combine harvesting (reaping and threshing) process. We learned a lot that way, and gradually worked out the best combination of power, force applied, threshing process and the best kind of threshing drums for our aim of creating a small combine harvester, which would be cheap and suitable for German farmers harvesting German fields.”

Yet the early stages of the project were very trying and frustrating for the development team. The prototype of the first CLAAS combine harvester was constantly breaking down in the field. It was a “front cutting” machine, simply “stuck on” to a Lanz Bulldog tractor, so it was already looking ahead to the idea of a self-propelled harvester. After being cut on the cutting mechanism at the front, the grain was conveyed around the tractor to be threshed at the rear. This was a very advanced approach, and also a courageous one. For the first public demonstration of the prototype, specialists from every segment of the agricultural sector came to watch in a field not far from Harsewinkel. However, the only harvest was not sackfuls of grain, but furrowed brows and shaken heads – the prototype had unfortunately broken down.

But they repeated the exercise the following year, already with better results. If only they could find even one industrial partner to shoulder the high development costs for such a major project, they thought. August Claas: “We loaded our second combine harvester model onto a railway wagon and took it to Zweibrücken. The management from Lanz came to take a look, smiled and shook their heads, and headed off to a local café to tell a few jokes – but not to talk about our combine harvester.”

At that moment, August Claas decided he was fed up with waiting for others to come on board. “If no one wants to join us, we’ll do it on our own”, he said, backed up by his youngest brother Theo in particular.

The combine harvester for European conditions celebrates its premiere

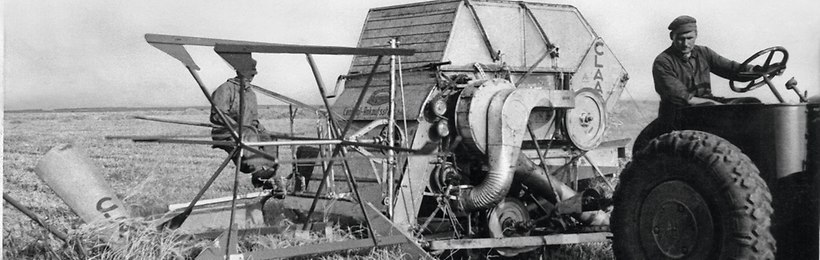

Debut in 1936. The first CLAAS combine harvester, a mower-thresher-binder (abbreviated MDB in German), hits the harvest fields.

After the outright rejection of its “front cutting” combine harvester, from 1935, the team focused solely on building a trailed machine. This time, they decided to play it safe, and return to the proven components of existing harvesting technology. The principle was a simple one:

- Take a traditional mower-binder machine and threshing machine.

- Split the mower-binder between the reaping platform and straw binder.

- Insert an ultra-compact threshing machine between the two halves, and join the parts up into one integrated machine.

And there it was – the CLAAS mower-thresher binder, or “MDB” for short (from the words in German). The record in the CLAAS combine harvester chronicle from the time reads as follows: “The result was a mower-thresher-binder (MDB) suitable for German conditions, a machine that reaped the crop, threshed the grain and bound the straw, all at the same time. Europe had never seen anything like it.”

For the 1936 harvest season, the machine bearing the serial No. 1 was delivered to the Zschernitz farm near Halle (Saale). “Getting the whole job done in a single step” was the slogan used in later company brochures promoting its mower-thresher-binder, designed by Dr. Ing. Brenner. Even the sector professionals were impressed with the benefits of the machine first developed specifically for German conditions: it reaped the crop like a binder-mower, threshed the grain like a normal wide drum thresher, bound the straw like a straw binder, carried out two grain cleaning cycles and separated it from the chaff. The new combine harvester would pay for itself from a farm area as little as 62.5 hectares, with a threshing yield averaging 15 to 20 tonnes of grain per day – a staggering yield for that time.

The new combine harvester generation

Already by 1942, the plans were ready for the new combine harvester generation, the CLAAS SUPER.

In 1939, the 100th CLAAS MDB machine hit the harvesting fields. In the war years 1940 and 1941, official restrictions allowed the production of only 450 machines a year in Harsewinkel. A total of almost 1,400 MDB machines were sold. Then, in January 1943, the government banned the production of combine harvesters altogether, and the business had to switch to the production of armaments. Yet this did not dissuade the team of developers supporting Dr. Walter Brenner and August Claas from undertaking further work on enhancing the design.

Already by 1942, the plans were ready for the third combine harvester generation, the CLAAS SUPER. Drawing on the experience gained from ten years of combine harvester development, six years of series production and the harvesting results of 1,400 MDB combine harvesters throughout Europe, the CLAAS engineers developed a combine harvester featuring outstanding technical reliability and cost efficiency. The mower-thresher machine (“Mähdrusch”) was to transform the crop farming landscape as no other machine apart from the tractor had done. This marked the beginning of an era in grain harvesting in Europe.

Chapter selection:

1913 – 1929: It all started with a knot

1930 – 1945: The combine harvester revolutionises harvesting.

1946 – 1968: Step up to combine harvester specialist status